Wednesday, April 22, 2009

Cloud computing on cell phones.

Now Technology Review reports on an experiment to use smaller, more efficient and far less power hungry computers for a farm. FAWN (Fast Array of Wimpy Nodes) is a server bank using the CPUs and memories from net book computers. For applications that just need to deliver small amounts of data, this approach turns out to be faster and cheaper than conventional servers. The reason being that the IO bottleneck is usually the disk reads. Thus using lots of small processors and DRAM memory for storage, the server arary can deliver more requests. The 2 papers to be published can be obtained from the author's website http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dga/ or directly from here and here. Interesting reading.

Which leads me to a further idea. Why cannot we use smart phones as a cloud? Here were have the fastest growing market for CPUs and memory. They are ubiquitous and sit idle for much of the day. What if they could be linked to offer a huge cloud for small messages? The phones would need to update the system with their current ip address and host some sort of lightweight web server. Security would need to be handled in a sandbox. If a webserver could be installed as part of the OS, there could be a distributed cloud that encompassed the globe. Running in memory on low power CPUs, just like FAWN, but with billions of nodes. Small, cheap and out of control. Indeed.

Food for thought.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Cloud Dynamics

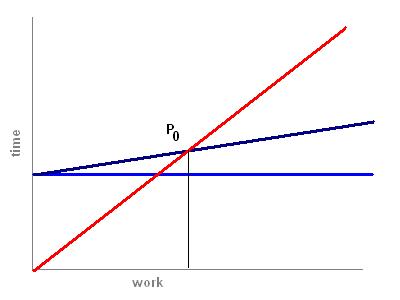

This is how I describe the dynamics of cloud computing. The first chart shows the model. The axes are computer workload vs. time to complete a task. The red line is for the client device, which is assumed to be less powerful than the server. The blue line is the latency of the connection to the server, the time it takes to deliver some data request and return a result. For a simple ping, this is of the order of 1/10 of a second or less, depending on traffic. Adding more data will increase the time as bandwidth is limited, which is why those Google maps can take forever to load on a smart phone over the cell network. The dark blue line is the total time for a request adding in the server's more powerful processing speed.

At point P0 is the break-even time. Tasks that take less work than this should be handled by the client device, while ones longer than this may be handled more effectively by the server, assuming the service wants to offer the shortest response time.

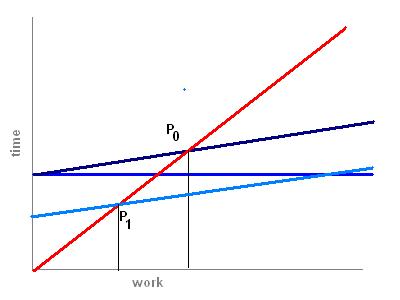

The next chart shows the effect of different clients. A PC is faster than a smart phone, so the break-even point is shifted to the left with a lower powered device. This means that more processing should be handled by the servers.

The third chart shows the effect of lower latency. If you could make the connection faster, again the server should take more load. In practice, the latency is mostly due to bandwidth limitations as data is moved between local device and server. Increasing bandwidth therefore makes servers more attractive.

The fourth chart shows two extremes. The vertical orange line is for a dumb terminal that cannot do any processing. This isn’t an obsolete idea. Ultra thin clients might want to have no processing at all, e.g. to display signs, or just may want to prevent any processing at all. You can do this with your browser by turning off Java and Javascript.

The horizontal green line assumes that the server is infinitely scalable, rather like Google’s search engine. In this case, almost any task is computable in a short time.

So what does this tell us about the future? Firstly we know that the fastest growing market is the mobile market, whether smart phones or the new net books. This suggests that the drive to increase server processing in the cloud is going to increase dramatically. Desktop PCs and workstations however, will not likely benefit from the cloud doing the processing, so we can expect big applications to remain installed on the local machine and using the cloud simply for delivery of updates to the software.The war over bandwidth pricing implies that the providers will effectively keep bandwidth low and rates high, shifting the break-even to more local processing and hence driving up the demand for more powerful local devices. This will tend to stifle the growth of ultra thin client devices if unchecked.

For me, the interesting story is what happens if we can build extremely powerful servers, able to deliver a lot of coordinated processing speed to a task. In this case is may make a lot of sense to offload processing to the server like we do with search. One way to think about this is with the familiar calculator widget. Simple 4 function or scientific calculators can easily compute on the client, so the calculator is an installed application.

But what if you want to compute hard stuff, maybe whether a large number is prime? Then it makes sense to use the server as the task can be made easily parallel across many machines and the result returned very quickly indeed. Now the calculator will have more functionality, doing lightweight calculations locally and the heavyweight ones on the server. This approach applies to a lot of tasks that are being thought of today and is driving the demand for both platforms and software languages that can make this very easy to achieve.

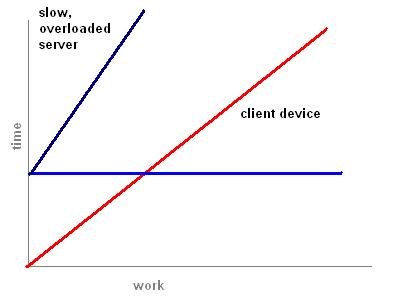

Finally, let's look at a case where the server is slower than the client. There is no break-even point because the client device is always faster than the server.

This scenario of the early days of the networked personal computer. Those were the days when networks were slow and servers, if they existed, were mostly simple file servers. It was also characterized by the period of extremely low bandwidth modems, preventing any reasonably fast computational turnarounds. In that world, it made sense to distribute software in boxes and install it on the client. This is still the dominant paradigm, even today, but it is clear that the advent of server farms and broadband, plus the demand for more lightweight mobile devices, will drive the cloud computing paradigm.

Stay tuned...

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

Courtesy of Marketing, Everything is Cloud Computing

And so it went at a talk I attended last night. The talk was entitled

The Business Value of Cloud Computing

and we had two engaging industry people talking about the cloud from opposite, but possibly complementary corners.

In the right corner was Paul Steinberg of Soonr.com. He spoke generically about SaaS (Software as a Service) and rolled out the usual suspects, GMail and Zoho Office as examples of this trend. Now I ask you, if GMail was delivered via a mainframe, would it suddenly lose it's cloud status? But conversely, if I throw up a web page on my ISP delivered website that has a rich client application in the page, would that be SaaS or cloud computing? At one point Paul said "SaaS is the same as cloud computing". Once the sales and marketing people get loose, you know the hype machine is in full swing.

In the left corner was Zorawar Biri Singh, from IBM. Biri presented us with some corporate IBM slides in a dizzying fashion, never allowing anything to be viewed in detail or explaining much. His role appeared to be to tell eveyone that IBM was in the cloud game and that their experience and dominance (in high end services?) would bring forth the goods in this arena. He had a couple of interesting details. Firstly, virtual machines were rapidly outstripping hardware machines. (Go out and buy VMWare NYSE: VMW ?) Secondly that while Amazon is selling CPU time for 10 cents an hour, he thought that the real cost might be closer to half a cent an hour. Do I hear 'supernormal profits' and IBM's rush to participate? One member of the audience questioned what sustainable advantage IBM might have in this game? Answer: "waffle, waffle, blah, blah, waffle". We've seen IBM do this before, last time it was SOA (service oriented architecture). IBM's solution was typically expensive and required a lot of IT and programmer time. Bottom like for Biri - cloud computing cuts costs. And IBM will be just the company to help you do that, no really.

So it looks like IBM is looking to build a rich server platform in the sky.

The problem with the cloud computing hype is that the customer doesn't care how the server parts work. In the same way I don't really know what fuels are delivered the power to my house. All I care about is that it is there and complain about it when the summer blackouts arrive. Most customers care about what it means for them. Is their client machine software going to be installed or web delivered? What feautures does it have? What does it cost? Where should teh data reside, and if the cloud, is it secure? Increasingly it will be "Can I get access to my software and data from any device, anywhere?". And increasingly that will mean mobile devices, from laptops to smart phone sized ones.

What few vendors talk about, is that the really power of the cloud is that software and data will increasingly be able to talk to each other out of their silos. That software will be able to draw on other software and data using a lot of resources to deliver really powerful information processing and delivery services.

Then the rain will fall on all of us.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Web 2.0 Sensorium

The defining characteristic of Web 2.0 for me is Tim's "harnessing collective intelligence" meme. I've been interested in "intelligence" ever since I saw Hal 9000 when I was 14. In the early 80's I was avidly reading Hofstadter's "Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid". More recently I have been interested in swarm intelligence, and now E. O. Wilson has written "The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies" which puts ants firmly in the group intelligence sphere and is re-positing the previously discredited the idea of evolution at the group level.

So what has this to do with accessing the web? If Web 2.0 is about collective intelligence, or how the actions of all the participants generates meta information, we can see the parallels between humans participating in a group mind and ants as part of a colony mind. But whereas ants cannot see the big picture as they mindlessly toil, we humans can do do, or at least, see fragments of it reflected back to us. A good example is Amazon's book suggestions which offers me a lot of information on the quality of a book from reader's purchases and feedback. In effect, Amazon offers me access to the group mind's view of the book, and effectively enhances my book buying cognitive processes. Wikipedia, and other data look up services, is like an extended memory. And here's where we get to the point. I don't want my extended memory and cognive processes turned off when I leave my PC. My brain is mobile by definition. If Web 2.0 is going to increasingly become part of my mind. Today that access has reduced bandwidth and resolution when I use my phone. It's like looking at the world through a rolled up newspaper. But, since my brain is mobile, my access must be too, however limited in scope. It is arguably even more important to be connected to the group mind when I am away from a PC, and as that mind expands, that will become ever more important. The cell phone has become the ubiquitous personal communication device. It is highly portable. Coverage is global. And "smart phones" like the iPhone are bridging the gap between PCs and basic phones. But clearly they will be used differently, much like calculators were not used like mainframe computers. Phones will become connection between my brain and the group brain and thus will need to use their limited bandwidth to efficiently to get me the salient information from that group mind - "What are the good restaurants nearby? Is this restaurant good? How much wil it cost me for a meal? What are the popular dishes and combinations? Has anyone I know eaten here recently? Has the health inspector shut down the kitchen in the last year?" and of course adding my information to the mind, much like an ant adds a drop of pheromone to the sugar trail.

It's early days of course. I would like my phone to have a screen that can be made larger, more like a paperback book, and definitely faster data transfer. The interface to use the device could be a lot better, But I think the trend is obvious to an observer. The mobile web is transitioning to become the dominant paradigm, leaving the richer, PC based access to different usage patterns. This seems to me another of the "good enough" devices that will undermine the use of PCs for web access for anything but the more specialist roles that need its power.

Monday, October 27, 2008

SETI - Day of Science

It started off well, with a stimulating lecture about using information theory to describe the complexity of animal languages as a test on what to look for in alien signals. The technique was applied to dolphins and humpback whales, showing that the sounds they made and their usage appeared to indicate that they were languages. Particularly interesting was the observation that baby dolphins babble like human infants before acquiring the adult sound patterns. The problem for the detection of alien signals is that if they are encrypted to maximize transmission, all this pattern is lost as the signal entropy is maximized. So we have to hope that the signals are unencrypted.

This was followed by a rather tedious lecture about the precautions needed to prevent contamination by spacecraft and humans on other planets. While we all want to preserve any living organisms on other planets, I couldn't help feeling that this was the ultimate stalling environmental impact report approach, designed to stymie any serious exploration of the planets where life might occur. Very noble, but if Columbus had had to comply, he wouldn't have bothered to make the trip.

We then received a trio of lectures on the Kepler space telescope that may be able to detect earth sized planets around other stars, the early plans for a Europa mission, and a session on the philosophy behind what should we do if we actually receive unambiguous alien signals. The Kepler mission will probably be getting data for it's first discoveries in a couple of years, the Europa mission probably won't happen until the 2020's, if at all, and I seriously doubt we will receive signals from aliens in my lifetime.

The last part of the program brought on the SETI rock stars. Jill Tarter, who has just won the 2009 TED prize, described the neww Allen Taelescope Array in northern California. I was pleased to hear that it was primarily for doing high resolution ratio telescope work, and only secondarily for alien signal detection. Most fascinating was the effect of Moore's lw on electronics affecting the size of each radio dish. Another few years and they might be small enough and cheap enough to buy at Radio-Shack. Then Seth Shostak took the stage to regale us with a very humorous presentation on the reasoning behind the SETI strategy. definitely a fun talk, but it was clear that SETI makes some huge assumptions about the aliens and thus the nature of the signals SETI hopes to listen for, namely very short, high strength, beacon signals that repeat over longer intervals, perhaps a week, perhaps a year.

IMO, the SETI approach feels very similar to the 19th century idea of buring huge forest fires in a geometric shape as a way to signal to the Martians. SETI assumes that the aliens will use radio ways (or at least the electro-magnetic spectrum) and that they are only located on their home star, and therefore likely to be far away. This just strikes me as incredibly conservative. Aliens could easily determine likely life bearing planets, as we are just about to do today, maybe even pinpoint actually planets bearing life. Then they could send small probes to those planets to monitor them. If they wanted to communicate, a local signal could be generated, much like Clarke's monolith. And if they can send small probes, and they might be very small, then maybe they can communicate at FTL speeds, perhaps using quantum entanglement. In other words, we are assuming aliens will be using a level of technology extrapolated from ours, rather than what an advanced race might really use.

After the program I sopke to Shostak about his assumptions and he agreed, that all bets were off if the aliens were not remote but were indeed scattered through the galaxy. But I accept that we have to start somewhere, so we might as well look, especially as the new ATA will give us that capability almost for free, piggy-backing on mainstream astronomy.

Monday, October 13, 2008

GWT version blues

But sometimes the boys and girls at Google can be very annoying.

Last week, after returning to make some changes to Skollar, I noticed that some core pieces of my application had stopped working. I suspected it was the GWT libraries, as a version that I had on Amazon's EC2 was still working fine, whilst a development version on a local server using the same codebase but a newer GWT library was not. I tracked the problem down to a change in the Element class API. Previously, when I needed to get an outerHML String, I used the toString() method on the Element instance. But as of v1.5, toString() no longer has this behavior which is replaced by getString(). Is this rather important API change mentioned in the release notes? If it is, it is obscure, and I cannot find a direct reference to this change. Now if I was part of the GWT development team, I would have asked for this change to be made obvious in the documents and I would have used getOuterHTML() instead of getString() to make this change more obvious to the developer.

Fortunately the code changes were simple to fix this time, but I wish the Google folks would think a little more before they release the next beta.